Food is a basic necessity. But you can never truly understand its importance until you have experienced a life without it.

When I first reached boarding school, I left my parents behind. I left my home behind. And, last but not least, I left my food behind.

Back home, I was the “spoilt one.” My mom cooked anything and everything I fancied. I was so selective that anything outside my “favorite zone” was a strict no-go. I even shouted at my mother if she cooked something I didn’t like. She never complained—she just quietly went back to the kitchen to make something else. Looking back, it must have been hard for her, watching her son reject her effort over a matter of taste, unaware of how fragile abundance really is.

Then came school, and food became a crisis.

The taste was alien, almost hostile. It was beyond my imagination to swallow it. I stopped eating almost entirely. One chapati in 24 hours was all I could ingest without vomiting. I lost so much weight that when I finally went home for holidays, my own family struggled to recognize me. Hunger does that—it erases familiarity, even from the face you thought you knew.

The lack of food led to extreme weakness. I would grow dizzy and collapse on the floor without warning. My favorite foods were available in the school canteen—samosas, patties, sweets—but food there cost money. And I had none.

Desire was visible, reachable, and still unattainable.

One day, in the luggage room of my hostel, I found a 20-rupee note lying on the floor. It was crisp, blue, and inviting. It must have belonged to one of my classmates, perhaps fallen from a pocket while unpacking. A small thing, easily ignored—unless you were hungry enough to notice it.

My entire upbringing, every moral lesson my parents had taught me, commanded me to pick it up and give it to the warden. But my stomach commanded otherwise.

Needless to say, the body dominated the conscience.

I picked up the note, my heart racing, and walked straight to the canteen. I bought two samosas. I ate them in a frenzy. For a few minutes, they felt like nectar. They felt like life returning to my limbs. Hunger doesn’t ask philosophical questions; it demands obedience.

I returned to the hostel only to find the child who had lost the money standing in the hallway, cursing the thief. He was angry, venting his frustration to anyone who would listen. His anger was loud. My guilt was silent.

I knew what I had done. And to save face, I joined him—abusing the thief. Abusing myself. Shame has a strange instinct for self-preservation.

Given his attitude toward me from that day onwards, I suspect someone saw me pick up the money, spend it, and then pretend otherwise. My hunger had turned me into a thief—and a target of quiet, persistent abuse that lasted for months. The food was temporary. The consequence was not.

That 20-rupee note taught me a lesson that no textbook ever could. Food is a basic necessity. And respecting even the tiniest grain is as important as respecting a life. When you are full, a grain of rice is trash. When you are starving, it is gold. Hunger recalibrates value with brutal honesty.

Thousands of years ago, a sage understood this truth far more deeply than I did. But while my hunger led to shame, his hunger led to the discovery of the atom.

The Legend of the Grain Eater

In the ancient spiritual landscape of India, the focus was almost entirely on the “Big Picture.”

Most sages looked upward—scanning the stars for cosmic order. Others closed their eyes to discover the infinite Brahman within, teaching that the physical world was Maya (illusion). To find truth, they taught, one had to transcend the material.

But one man looked down.

His name was Kashyapa. He lived around the 6th century BCE (though timelines in Indian history are often fluid), near the holy city of Prayag. Traditional accounts say he lived an ascetic life of extreme austerity. But unlike other monks who begged for alms or relied on royal patronage, Kashyapa chose a different discipline—one that trained attention rather than withdrawal.

He walked through harvested fields after the farmers had gone home. He scanned dusty roads after trade caravans had passed. He wasn’t looking for gold or lost jewels.

He was looking for broken, trampled grains of rice—discarded fragments crushed into the dirt, noticed by no one because they were too small to matter.

He would patiently pick them up, one by one. He spent hours cleaning the dirt off each fragment, washing them, collecting enough to make a meager meal. To a passerby, this appeared absurd. Why would a learned sage, a man of immense intellect, scavenge for what even beggars ignored?

When asked why he bothered with such insignificant scraps, his reply planted the seed of an entire philosophy:

“An individual grain may seem worthless. But a collection of grains makes a meal. A collection of meals sustains a life. And it is life that sustains the world.”

For Kashyapa, the small was not insignificant—it was foundational.

He realized something radical: the “Big” creates nothing. The “Big” is only the visible outcome of countless small things coming together. Ignore the particle, and you lose the universe.

Because of this habit, people began calling him Kanada—from Kana (grain or particle) and Ada (eater). The name likely began as a tease, a nickname for the “crazy grain eater.” He wore it as a title.

He was the Atom Eater.

This obsession with the smallest unit did not stop at rice. Kanada extended the same logic to reality itself. He began to look at the physical world not as an illusion to escape, but as a puzzle to understand.

If a mountain is a collection of stones, and a stone is a collection of sand, what is sand made of?

You can crush a stone into dust. You can crush dust into finer powder. But can this continue forever?

Kanada argued it could not. If division were endless, matter would have no structure. Eventually, you must reach a stopping point—a particle so fundamental it has no parts. If it has no parts, it cannot be cut. If it cannot be cut, it cannot be destroyed.

He called it Parmanu—the ultimate particle.

Long before particle accelerators, long before microscopes, and centuries before Democritus would coin atomos in Greece, the Grain Eater arrived at the atom. Not by smashing matter apart in a lab—but by respecting the smallest things enough to think clearly about them.

The Logic of the Universe (Vaisheshika Sutras)

Kanada didn’t stop at discovering the atom. He understood that if reality is built from distinctions, then freedom depends on understanding those distinctions correctly.

He founded the Vaisheshika school of philosophy—named after Vishesha, meaning particularity or distinction.

While other schools focused on how everything is One, Kanada asked a more dangerous question: What happens if we ignore difference?

His insight was brutally simple: ignorance arises from confusion. We suffer because we confuse pain for pleasure. The body for the self. The temporary for the eternal. The rope for the snake in the dark. Liberation, for Kanada, required precision. To be free, we must categorize reality accurately.

He divided the universe into six fundamental categories (Padarthas).

1. Dravya (Substance)

What is the universe actually made of? Kanada identified nine substances, refusing to separate physics from metaphysics.

The Physical: Earth, Water, Fire, Air, Ether.

The Abstract: Time and Space.

The Conscious: Self and Mind.

Time and Space were not metaphors. To Kanada, Time was as real as a rock—a container in which all events unfold. Confuse this, and you confuse your place in reality.

2. Guna (Quality)

If substances are hardware, qualities are the software. Qualities cannot exist independently. “Red” cannot float in the air; it must belong to something. Kanada listed 24 qualities, including pain and pleasure. His warning was existential: do not confuse the Quality with the Substance. You experience pain—but you are not pain. Qualities change. The Substance endures.

3. Karma (Action)

Matter moves. Kanada classified motion into five types: upward, downward, contraction, expansion, and locomotion. Every movement carries consequence. Nothing moves freely. Nothing moves without cost. This is why small actions are never small.

4. Samanya (Generality)

How do we recognize patterns? Why do we learn at all? Because things share universals. A cow is recognized as a cow because it shares cowness with other cows. Without Samanya, the world would be unintelligible chaos.

5. Vishesha (Particularity)

At the deepest level, everything is unique. Even atoms with identical qualities remain irreducibly distinct. Difference is not illusion—it is built into reality itself. Comparison, then, is metaphysically false.

6. Samavaya (Inherence)

The superglue of existence. Some bonds are separable; others are not. Remove heat from fire, and fire ceases to exist. Remove parts from a whole, and the whole disappears. That inseparable bond is Samavaya.

The Atomic Theory: A Logical Necessity

Kanada proved the atom through logic.

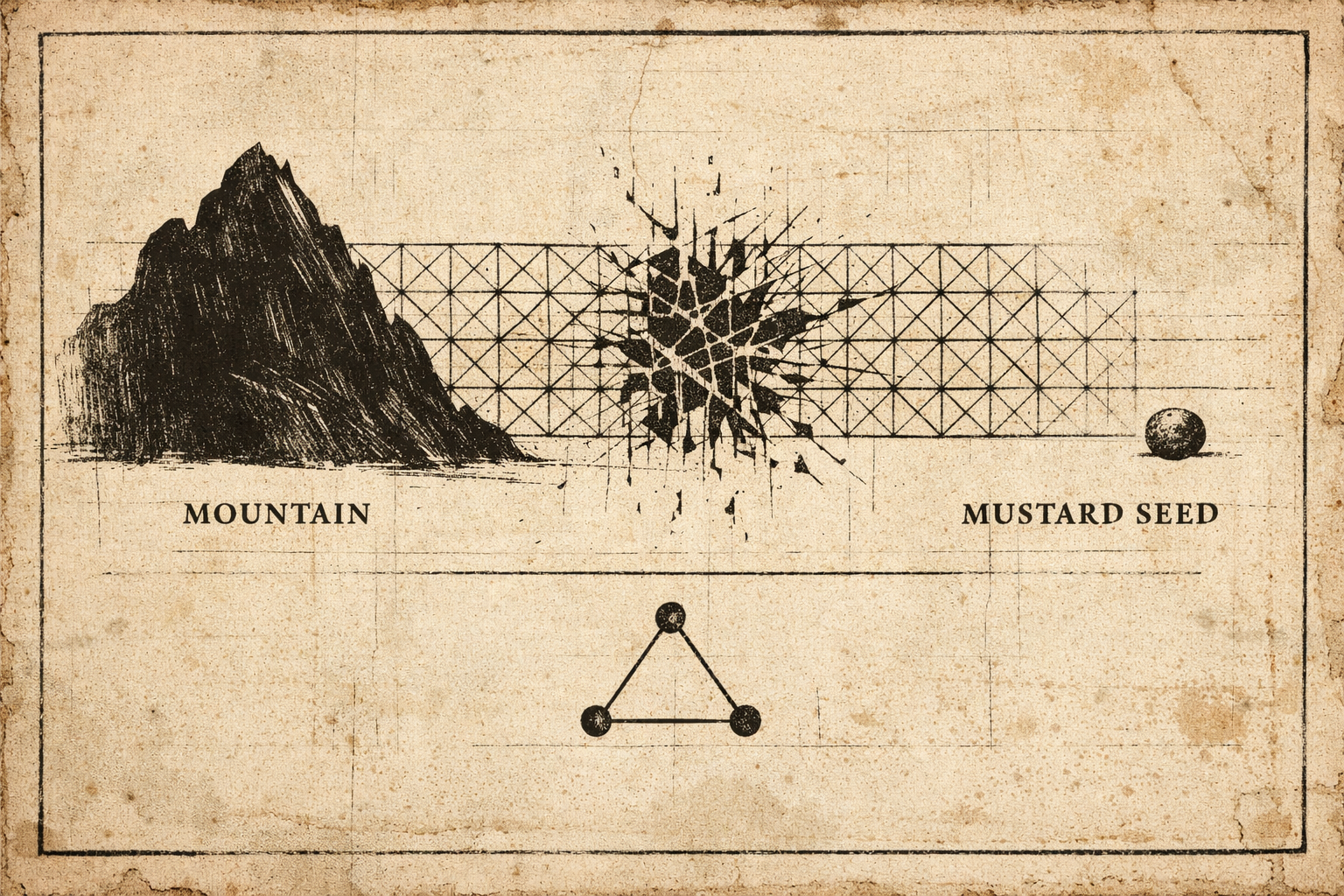

If matter were infinitely divisible, a mountain and a mustard seed would both contain infinite parts—and therefore be the same size.

They are not. Therefore, division must stop.Thus, the atom must exist. He described its combinations:

Parmanu: indivisible, eternal.

Dvyanuka: two atoms.

Tryanuka: three dyads—the smallest visible particle, like dust in sunlight.

This was not mysticism. It was ruthless metaphysical reasoning—the first serious attempt at a Standard Model of reality.

The Missing Link: The Unseen Force

Yet one question remained: Why does anything move at all? Physics explains how atoms combine. It struggles to explain why.

Kanada proposed Adrishta—the Unseen—not as blind belief, but as a metaphysical hypothesis. Karma, accumulated across beings, acts as a structuring force, pushing atoms into worlds where consequences can unfold.

The universe is not a dead machine. It is a morally structured stage—built from atoms, arranged by karma.

Just Think Over It

In that hostel luggage room, when I picked up the 20-rupee note, I wasn’t merely moving paper.

My hunger was a Quality. It moved my body, a Substance, to perform an Action. That action created a consequence.

The pleasure lasted minutes. The shame lasted months.

We obsess over the Big—big salaries, big houses, big impact. We ignore the small. But the Big is only a collection of the Small.

Corrupt the atom, and you corrupt the mountain. Corrupt the moment, and you corrupt the life.

Kanada teaches us to look down. To the grain. To the nuance. To the action that quietly builds the universe we must live in.

Respect the grain. Respect the atom. Respect your actions.

Just think over it.