I. The Petri Dish of Ego

Two decades ago, I lived inside the enclosed ecosystem of a co-educational boarding school. It was a compressed civilization, a petri dish where hormones, proximity, ambition, insecurity, and developing egos fermented under constant social scrutiny.

In that pressure chamber, every glance mattered. Every whisper traveled. Every rejection echoed.

I witnessed a phenomenon there that I have never been able to forget. It was not an isolated incident; it was a recurrent pattern. And it explains far more about adult relationships—and the failures of modern dating—than we are comfortable admitting.

I watched boys approach girls with a volatile mixture of bravado, entitlement, and raw nerve. They mistook audacity for charm and persistence for romance. And when rejection came—as it inevitably does, and as it absolutely should—I watched something unsettling unfold.

Their “love” did not fade. It inverted.

The humiliation of rejection triggered something primitive. The ego could not tolerate the simple truth of incompatibility. It could not accept the statement: “She does not want me.” That sentence was too clean, too final, and too damaging to the self-image. So, the mind manufactured a more tolerable narrative—one that preserved superiority.

Overnight, the girl transformed in his story. She was arrogant. She was “characterless.” She was playing games.

Rumors began to circulate. Respect became intimidation. Any boy who treated her normally was subtly warned off or openly confronted. What began as attraction mutated into character assassination.

It was a scorched-earth psychology: If I cannot possess the object of desire, I will destroy its value.

From the girl’s perspective, this was psychological warfare. A random boy approaches you. You exercise your dignity of choice. And as punishment for that agency, your reputation is dragged through the mud. You become the villain in a narrative you never consented to enter.

We dismiss this as teenage immaturity. Hormones. Drama. “Kids being kids.” But that is a convenient simplification.

What I witnessed was something far older and far more universal. It was Uncivilized Desire. It was instinct ungoverned by intellect, impulse unrestrained by ethics, emotion unmoderated by reflection. It was the animal self—the Pashu—erupting without the discipline of the human self—the Manava.

It was Kama (Desire) without Dharma (Order). And that phenomenon did not disappear when we graduated. It simply grew more sophisticated.

History, however, has already offered a remedy for this pathology. In one of the great ironies of intellectual history, the man who articulated that remedy has been reduced to a cultural joke.

II. The Great Paradox

Mention the name Vatsyayana today, and the modern imagination reflexively collapses into caricature: awkward smiles, exaggerated contortions, and the label of “ancient sex guru.” He has been flattened into a mascot for indulgence, his name invoked more often in locker room humor than in university lecture halls.

This reduction is not merely inaccurate. It is an intellectual tragedy.

The truth is colder, sharper, and far more impressive. Vatsyayana was most likely a Brahmachari—a celibate scholar devoted to disciplined study. The Kama Sutra was not a memoir of personal exploits; it was an analytical treatise. He observed human behavior with the detachment of a logician, not the appetite of a libertine.

He lived during the Gupta period (approx. 2nd–4th Century CE), a time of extraordinary cultural and intellectual refinement, perhaps in cities such as Pataliputra or Varanasi. These were not chaotic backwaters but thriving centers of administration, trade, art, and scholarship. Within this environment, Vatsyayana undertook something ambitious: he attempted to classify human desire.

He understood what the boarding school bully did not: Desire, left to itself, becomes coercive. Passion without discipline mutates into aggression. Attraction without refinement degenerates into entitlement.

But to see him merely as a sociologist of pleasure is still to miss the scale of his mind.

Before he categorized the arts of love, Vatsyayana secured the foundations of reality itself. He authored the earliest surviving commentary on the Nyaya Sutras, aligning himself with one of the most rigorous intellectual traditions in classical India. He was not a hedonist dabbling in metaphysics. He was a logician who later applied his structural intelligence to human intimacy.

He was not a lover who occasionally reasoned. He was a reasoner who refused to exclude love from reason.

To understand him, we must stop imagining a romantic mystic and start recognizing an Architect of Systems.

III. The Architect of Reality: The Nyaya Foundation

To understand why Vatsyayana wrote about sex, you must first understand his “Day Job.” He was a Niyayika—a Logician.

At the time Vatsyayana lived, the intellectual climate of India was intensely contested. The Nyaya School (Logic and Realism) found itself in a cage match with powerful strands of Buddhist thought, particularly the Vijnanavada(Consciousness-Only) school.

The Buddhist argument was subtle and psychologically persuasive: “The world is an illusion.” They argued that dreams appear real while we are dreaming. Only upon waking do we recognize their illusory nature. How, then, can we be certain that waking life is not itself another layer of dream? If experience is mental, if perception is constructed, perhaps the world itself is merely a projection.

If that argument succeeds, everything destabilizes. If the world is a dream, then actions have no consequences. Ethics becomes provisional. Social structures lose objective grounding. If the world is fundamentally illusory, the urgency of discipline diminishes.

Vatsyayana recognized the danger. Civilization depends on the assumption that reality is not optional.

1. The Defense of the External World

In his commentary (Bhashya), Vatsyayana dismantles the dream analogy with a devastating piece of logic known as the “Double Standard” proof.

He argues that the concept of “Illusion” is parasitic on the concept of “Reality.” A counterfeit coin is meaningful only because genuine coins exist. A mirage deceives precisely because real water is known.

“If there were no real objects perceived in the waking state, there would be no memory of them to construct the dream state.”

Dreams borrow their material from waking experience. One can dream of an elephant because elephants—or at least their perceptual components—have been encountered in waking life. Without prior real perception, there would be no content from which dreams could assemble their illusions.

Thus, the illusory depends upon the real. To deny reality, one must rely on the conceptual tools supplied by reality. The argument collapses into self-defeat.

This was not abstract hair-splitting. It was foundational. Vatsyayana secured a philosophical ground upon which science, ethics, and social order could stand. Facts, he insisted, are not dissolved by feelings. The world exists independently of our preferences.

2. The Discipline of Inquiry (Anvikshiki)

He also articulated the discipline of inquiry itself. He distinguished between:

-

Samshaya (Doubt): The starting point of knowledge.

-

Nirnaya (Conclusion): The end point of knowledge.

The bridge between them is Nyaya. Vatsyayana insisted that every argument must have a Prayojana (Purpose). Thinking was not for idle speculation; it was a tool for Action.

And here lies the crucial insight: When this same mind turned toward Kama (Desire), it did not abandon rigor. It extended it.

IV. The Architect of Society: The Kama Structure

Only after he had secured the existence of Reality did he turn his eyes to the messy business of living in it.

The Kama Sutra is frequently mistaken for a catalog of physical techniques. In reality, it is a manual for Civilized Living within an urban society. It was written for the Nagaraka—the cultivated city-dweller. This archetype was not defined by raw wealth or brute strength, but by refinement, education, and social intelligence.

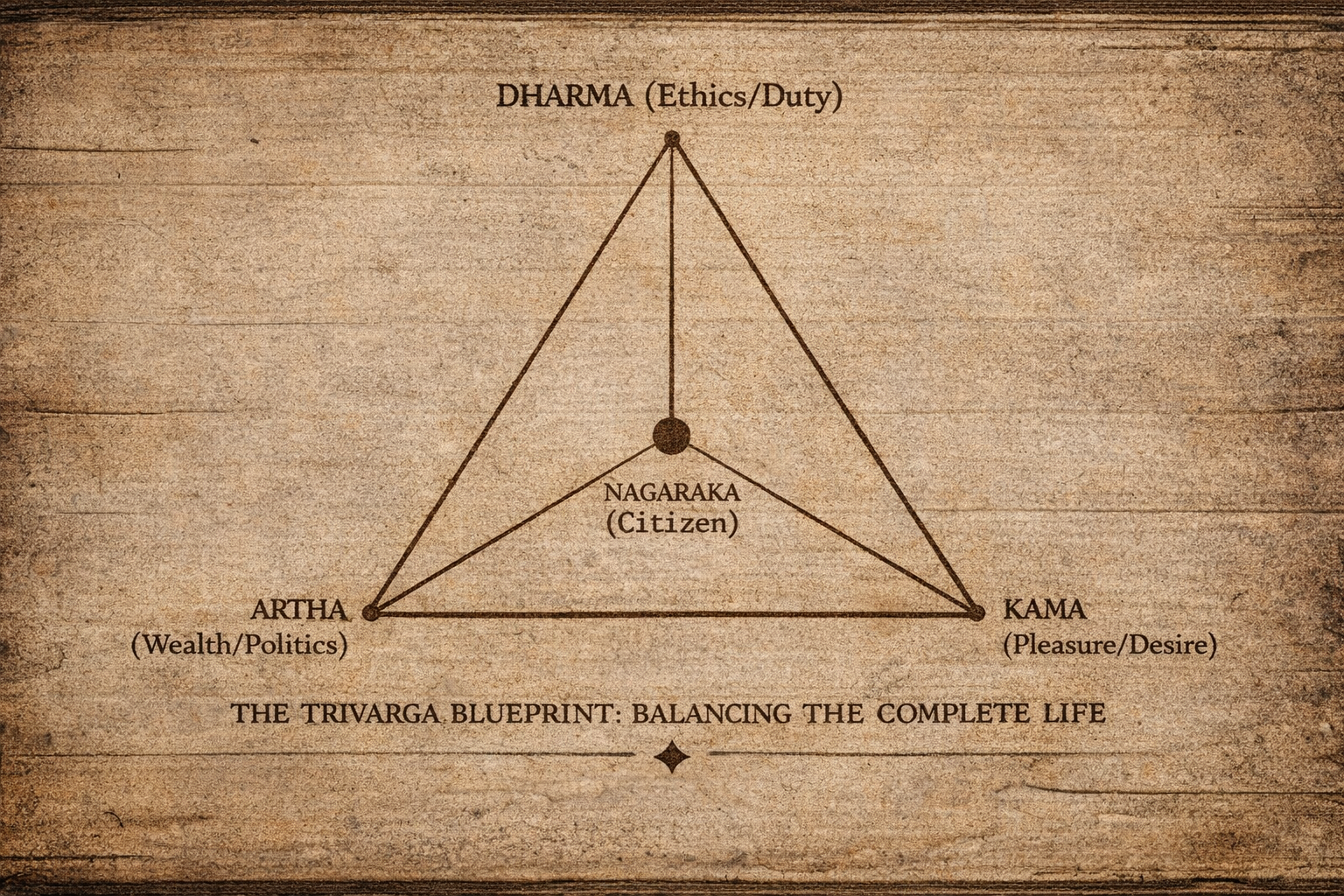

1. The Algorithm of Trivarga

Vatsyayana situates Kama within a larger framework known as the Trivarga (The Three Goals of Life):

-

Dharma: Ethical order and duty.

-

Artha: Material prosperity and politics.

-

Kama: Cultivated pleasure and aesthetics.

These were not rivals; they were interdependent variables in the equation of a good life.

-

A life governed solely by Dharma risks austerity without joy.

-

A life driven only by Artha becomes cold and acquisitive.

-

A life surrendered entirely to Kama collapses into instability.

The Trivarga Blueprint: The Vatsyayana Algorithm for a complete life.

The Vatsyayana Rule:

“Any act that satisfies all three is the Best. Any act that satisfies two is Good. Any act that satisfies only one is Inferior. Any act that satisfies one at the expense of the other two is to be Rejected.“

Excessive indulgence erodes wealth (Artha) and reputation (Dharma). Yet repression of pleasure breeds brittleness. Pleasure, in Vatsyayana’s system, is legitimate—but only when harmonized with ethics and sustainability.

2. The Connection to Statecraft

Vatsyayana was intellectually descended from Kautilya (Chanakya). Where Kautilya wrote the Arthashastra to systematize statecraft, espionage, and political power, Vatsyayana wrote the Kama Sutra to systematize domestic and relational life.

The structural clarity is unmistakable. Vatsyayana treats a Lover exactly as Kautilya treats a King: someone who must manage resources, understand psychology, and maintain alliances. Administration and affection were not separate worlds; both required discipline.

V. The Psychology of the Rejected Boy

Viewed through Vatsyayana’s lens, the rejected boy from my school years was not tragic. He was Uncultured.

The Kama Sutra contains a surprisingly refined understanding of Consent and Agency. In an era where women were often treated as property, Vatsyayana argued for the necessity of female pleasure.

-

He states clearly that a sexual union is a failure if the woman is not satisfied.

-

He categorizes relationships not just by physical fit, but by emotional depth.

Vatsyayana also outlines methods of resolving conflict between lovers—Pranaya-kalaha. He advises conciliation (Sama), empathy, and symbolic gestures of value (Dana).

Crucially, he separates the tools of War from the tools of Love. Danda (Force/Punishment) belongs to political governance. It has no place in intimate bonds.

The boarding school boy resorted to humiliation and intimidation because he lacked subtler skills. He interpreted rejection not as incompatibility but as an insult to his status. Without intellectual discipline or emotional training, he reached for the only weapon available: destruction.

Vatsyayana would have recognized this immediately. It is the behavior of someone ruled by unregulated impulse. It is Kama divorced from Nyaya (Logic) and Dharma (Ethics).

VI. The 64 Arts: Competence Is Seductive

Perhaps the most misunderstood feature of Vatsyayana’s work is the famous list of 64 Arts (Chausath Kala). Popular imagination reduces them to erotic techniques.

In truth, they are a curriculum for a Renaissance Man. They include:

-

Prahelika: Solving riddles and puzzles (Logic).

-

Yantra-matrika: Mechanics and engineering.

-

Mlecchita-vikalpa: Cryptography and secret writing.

-

Vrikshayurveda: Botany and gardening.

-

Vastu-vidya: Architecture.

This is not indulgence. It is Cultivation. Attraction, in Vatsyayana’s framework, emerges from Competence. A person capable of reasoning, creating, repairing, appreciating beauty, and engaging in high-level conversation becomes magnetic not through aggression, but through presence.

To lack these capacities was to remain “rustic”—closer to the animal than the divine.

He democratized nobility. Birth was secondary. Mastery was decisive. The boarding school bully possessed ego, but not excellence. When rejected, he had no reservoir of cultivated identity to draw upon. He had built no depth beyond his immediate desire. And so, when desire failed, so did he.

VII. The Integrated Intellectual

Vatsyayana stands as a rare figure in history who refused fragmentation. He did not separate logic from love, economics from intimacy, or structure from pleasure.

He recognized that the same disciplined attention required to analyze the metaphysics of “Reality” is required to understand the emotional needs of another human being.

The rejected boy lacked integration. He experienced desire without reflection, emotion without proportion, attraction without self-development. His response to rejection revealed not passion, but a poverty of cultivation.

The modern world suffers from a similar fragmentation. We compartmentalize ourselves into “Professional Efficiency” and “Private Indulgence,” as though character does not cross those boundaries. We oscillate between repression and excess.

Vatsyayana offers a different model. Do not repress desire. Do not be consumed by desire. Civilize it.

He was not prescribing indulgence. He was prescribing integration. And perhaps that is why he has been misunderstood. A society uncomfortable with disciplined pleasure finds it easier to mock him than to study him.

But his message remains intact across centuries: The measure of a person is not the intensity of their desire, but the structure within which they place it.

That is not ancient trivia. It is civilizational advice.

Just Think Over It.